Campus Makes Plans to Expand

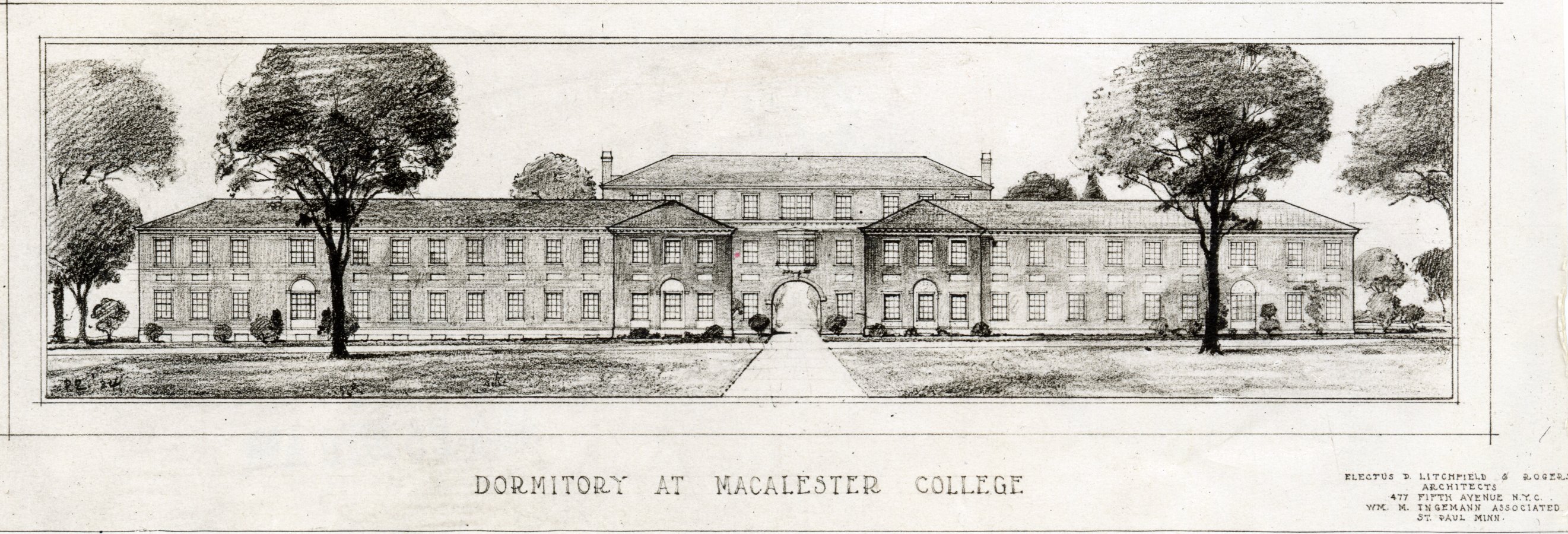

In 1926, Kirk Hall was constructed to house male students, the first dormitory for men constructed since the East Wing of Old Main. In contrast to the design of Wallace Hall, Kirk was built on the “Quadrangle Plan,” which consisted of a rectangular building looking down into an enclosed courtyard. Building dormitories in this style had a long history, including the oft-revered campuses of Cambridge and Oxford, however, the design gained prominence in the 20th century when administrators at Yale released a report titled “The Quadrangle Plan” in 1925.1 Art historian Carla Yanni explains that the report served as a guiding philosophy for higher education that focused on building community connections between students and professors and noted that “the compactness of the square donut plan promoted closeness among the students.”2

The quadrangle architectural form could also serve another purpose: surveillance and security. The design featured windows looking down on all sides onto a shared courtyard, creating a space physically separate from the rest of the neighborhood and somewhat reminiscent of the panopticon prison design, proposed by Jeremy Bentham in the 19th century. Michel Foucault later used the panopticon to symbolize the increased amount of government surveillance imposed upon society.3 As a college student, it was clear that privacy was not a priority when your outdoor courtyard space was in view of an array of windows. This style of architecture helped establish that college was a place where young adults would ideally learn and grow while still remaining under an appropriate amount of supervision— even if they no longer lived with their parents. Kirk Hall was built to encourage a close community among students, but its architecture also made it clear that students were far from living independently.

In addition to Kirk Hall, in 1929, the college’s president John Acheson developed a new plan to revamp the college’s curriculum and mission, which included a comprehensive plan for new facilities. The plan would lead to the construction of “at least six new buildings: a library, a classroom and administrative building, a science building, a chapel, a fine arts building, and a student activities building, each of which would be equipped with the most modern of facilities.”4 Unfortunately, the financial troubles of the Great Depression meant that Acheson’s plans had to be shelved, and they weren’t realized until after Acheson’s death.5 With the Great Depression, enrollment dropped, and the college had to reduce tuition in order to entice students back to the school. Funding received from rent on college owned property, primarily farmland in the north of Minnesota, dropped sharply.6 Any sort of college expansion would have to be put on hold.