Divisions in the Student Body?

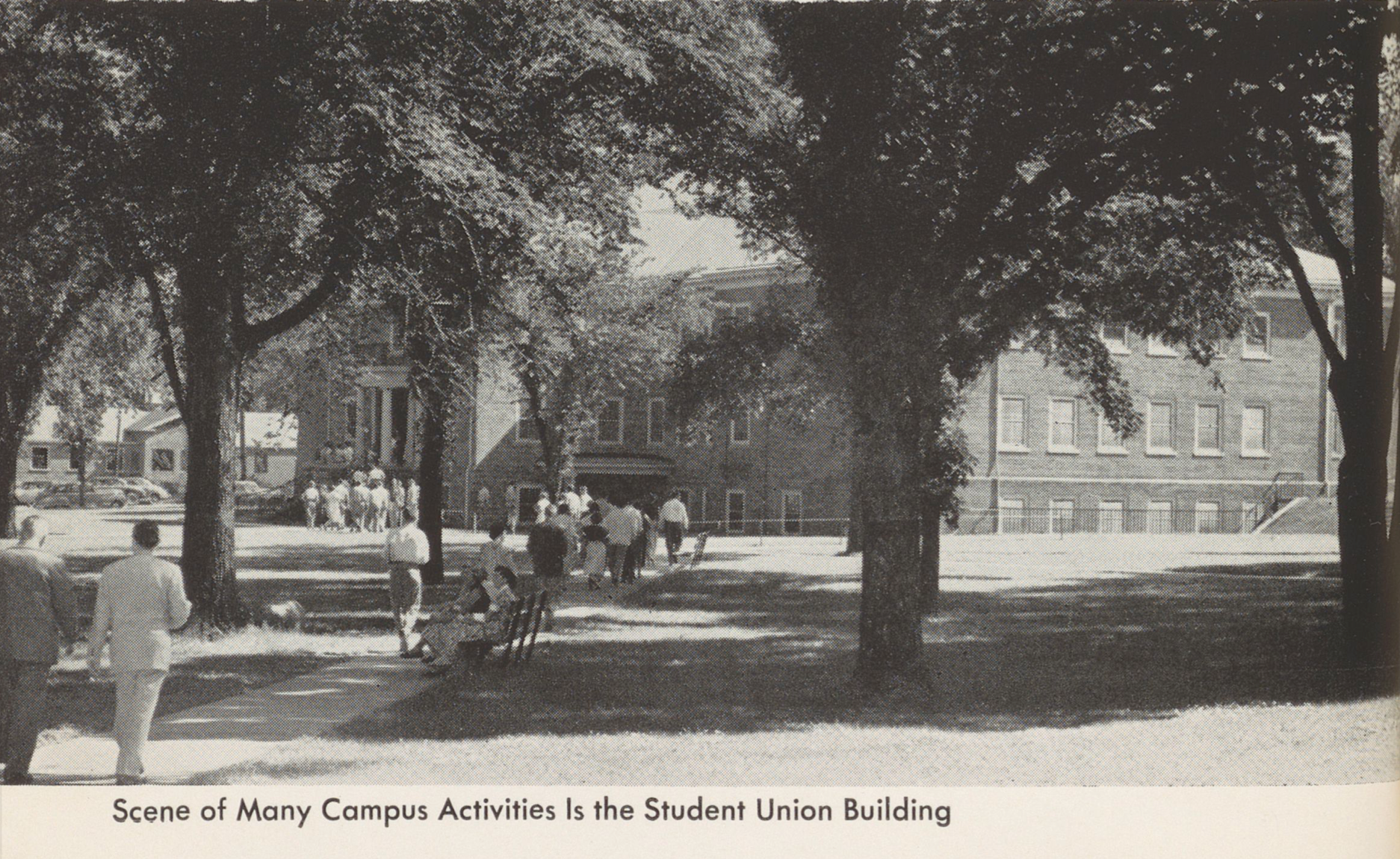

Despite the benefits offered by the new union, the building’s design also reflected the ways in which Macalester students and faculty were still divided. The union housed two separate lounges for faculty based on gender, with the men’s lounge featuring “card tables and a pool table,” while the women’s lounge had “sofas, a built-in dressing table and a full length mirror.”1 And although the new cafeteria served the male students who previously ate their meals in the dining room of Kirk Hall, the female residents of Wallace Hall and other women’s dorms still took their meals in their respective dorm dining rooms, which remained segregated by gender.2 Despite the union’s role as a central place on campus for all to lounge, the building’s design reinforced the structural separation of men and women on campus in ways that would prove to be problematic in the future.

Not long after the union opened, problems began cropping up in the cafeteria— in particular, long lines. When the women’s dining halls closed on the weekends, residents of those halls would instead eat at the union, creating a traffic jam. In a 1953 letter to the editor of the Mac Weekly, student Richard Morrill wrote that “[e]ating in the cafeteria on weekends is impossible with the crowd created by closing the girl’s dorm dining rooms,” meaning that “a large percentage of the off-campus students, Summit house girls and Kirk hall boys, who would like to eat in the cafeteria, must go out for their weekend meals.”3 Such problems continued to persist for years, until a new dining hall was constructed in the 1960s during a construction boom of new buildings on campus.

-

Janet Holloway, “Union? It’s Coming!”, Mac Weekly, October 19, 1951, Macalester College Archives. ↩

-

Cleo Waldhauser, “New Mac Union Promises Relief To Crowded Campus,” Mac Weekly, April 20, 1951, Macalester College Archives. ↩

-

Richard Morrill, “Old Gastric Problem Burps Up Once Again,” letter to the editor, Mac Weekly, January 16, 1953, Macalester College Archives. ↩